In 2020, author and journalist Wright Thompson traveled to Drew, Miss., for a private tour of a barn with a bloody and tragic history that many in the Mississippi Delta would like to forget.

The barn is where, in August. 28, 1955, a 14-year-old black boy named Emmett Till was brutally beaten and killed by two (and allegedly more) white men, who killed him for allegedly whistling at a white woman at a nearby grocery store.

The barn and surrounding property were bought in the 1990s by a dentist named Jeff Andrews, who despite having grown up in the area insisted Thompson knew nothing of its history before he bought it. Even more surprising, he was unconcerned about his barn’s grim legacy.

“It’s in the past,” he told the author, as Thompson recounts in his new book, “The Barn: The Secret History of a Murder in Mississippi” (Penguin Press), published in September. 24.

In fact, Andrews was convinced that they could go to any elementary school in the Delta and ask the kids about Emmett Till and 95% of them would have no idea who he was.

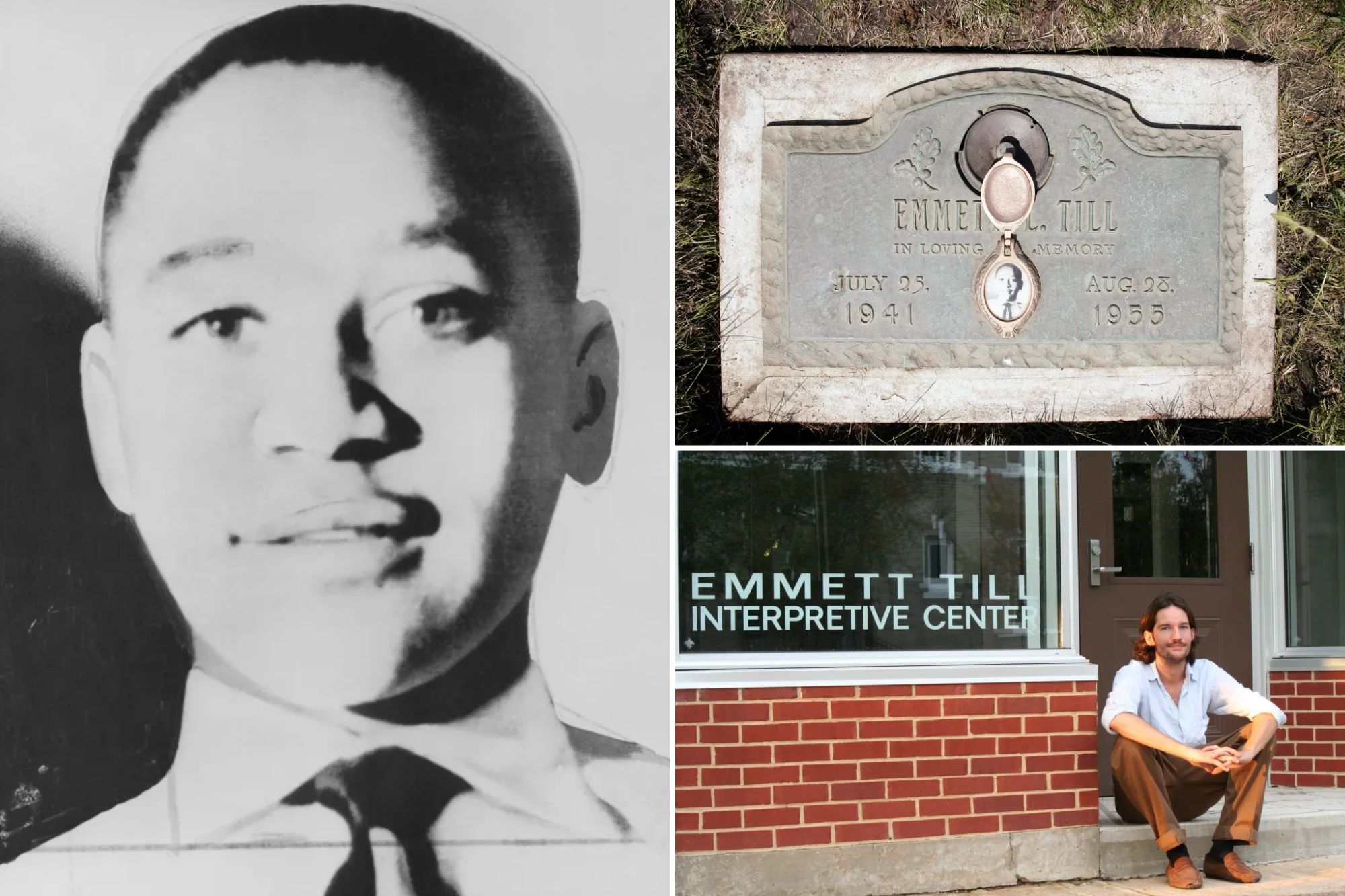

Today, Emmett Till is a civil rights icon.

When Americans gather to protest racial violence, Thompson writes, “someone almost certainly carries his picture, held aloft like a cross, no name needed.” But in the Delta, Till’s killing has been “almost entirely pushed out of the local collective memory.”

Thompson knows this first hand. He grew up in Clarksdale, Miss., 30 miles north of Drew, and had never heard of the barn until he met Patrick Weems, who runs the nearby Emmett Till Interpretive Center.

As Weems explained to Thompson, “If you go through Drew and stop and ask somebody, ‘Do you know where Emmett Till was killed?’ I think nine out of ten people will say, “What are you talking about?”

And it’s not just the white population trying to suppress the area’s sordid past.

Carl Watson, a black landowner who was born four years after the murder, just down the road from the barn, didn’t know Emmett Till’s story until his father told him in the late 1980s.

“Several generations grew up seeing the barn every day and never being told about it,” Thompson writes. “The white mothers and fathers in this part of Sunflower County didn’t talk about it. Neither did black mothers and fathers.”

For nearly half a century, the “official” story of the lynching came from journalist William Bradford Huie.

He sat down with Roy Bryant and JW Milam—who were acquitted by an all-white jury in 1955 of Till’s murder, and thus protected by double jeopardy laws—and published their accounts in Life magazine several months later.

Their version of events left out any mention of the barn, possibly to protect other associates, including the barn’s owner, Leslie Milam.

Over the years, efforts to preserve Till’s story, even the censored version, have met with stiff resistance.

Jesse Gresham, a local pastor in Drew, told the author that he once discovered a locked school board office full of history books about the civil rights movement, where they had been hidden for decades. “They don’t want to think about what their parents and grandparents did,” Gresham said. “They didn’t want future generations to know they were snakes.”

Weems shared a story about a teacher at the now-defunct Strider Academy — named after the sheriff who helped acquit Till’s killers — who assigned her students to research Till’s murder. “The kids came home and said, ‘Tell me about Emmett Till,'” Weems said.

The sweep over the years “has been sharp and brutally effective,” Thompson writes. The only copy of the trial record is long gone.

The gin fan used to sink Till’s body in the Tallahatchie River was kept by an attorney in Sumner “as a trophy,” but he eventually dumped it in a landfill.

The weapon used to kill Till is not melted down or in a museum, but is owned by a White Dust pilot whose father was given the murder weapon by Sheriff Strider. It still turns on.

The grocery store in Money, Miss., where Till allegedly blew the whistle on a white woman, Carolyn Bryant Donham, is now owned by Harry Ray Tribble and his siblings, children of one of the dead jurors from the murder trial in 1955.

He continues to insist that Till wasn’t actually killed — and the body was planted by the NAACP “to make Mississippi look bad and further a communist agenda bent on destroying liberty,” Thompson writes.

The gas station next door, also owned by a Tribble, was renovated in 2014 as a visitor center for civil rights tourists. It was meant to represent what life was really like in Till’s time, but actually “revels in the imaginary nostalgia of a racially harmonious Delta,” Thompson writes.

There are no separate bathrooms, but a jukebox where “white and black people came together to share the community of music.” There is no mention of Emmett Till.

Sometimes even allies, those trying to keep Till’s memory alive, can misinterpret history.

Wheeler Parker, 85, Till’s cousin and the last living eyewitness, once sat on a college panel dedicated to Emmett Till.

He heard the pope of scholars about his dead relative. When it was his turn to speak, Parker said, “I don’t think I know this guy you’re talking about. It was nice but it wasn’t right.”

These people were taking history and using it, Thompson writes. “Often for the better, but using it all the same. Changing details, messing up details, moving things around, making Emmett look better, or Carolyn (the white woman Whitt blew the whistle on) look better, exaggerations, excuses, white lies, mistakes. “

In 2008, the Emmett Till Memorial Commission erected a historical marker near the river where Till’s body was found.

It was replaced at least nine times, as the signs were stolen, or thrown into the river, or covered in hundreds of bullet holes.

It was a shadow retreat, Thompson writes, “with some people trying to preserve a memory and others trying, with guns, to erase it.”

A bulletproof marker was erected in 2019, and the bullet-riddled sign was donated to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

Plans for some sort of memorial at the barn have been longer in the making. Annual ceremonies have been held there every summer since 2022.

And last December, TV producer and writer Shonda Rhimes, known for hit shows like “Brigerton” and “Scandal,” announced that she was making a large donation to the Emmett Till Interpretive Center to help purchase the barn from Andrews and turn it into one. monument of Till.

A monument “would force a new conversation,” Thompson writes. “There is no heroism to remember here. Not defiantly. No one burst through the door in time, or risked his life for another, no one stood up to evil, no one stopped the torture.”

It’s an unpleasant reminder of our country’s shameful and violent past, but that’s exactly why this country needs to be preserved.

“The tragedy of humanity is not that sometimes a few depraved individuals do what the rest of us could never do,” Thompson writes. “It is that the rest of us. . . never learn the lesson that hatred grows stronger and more resistant when it goes underground.”

#murder #Emmett #remains #shrouded #racism #mystery

Image Source : nypost.com