In October. On the 26th, 1957, Reinhold Kulle and his family departed on the MS Italia from Cuxhaven, Germany, destined for a new life in America.

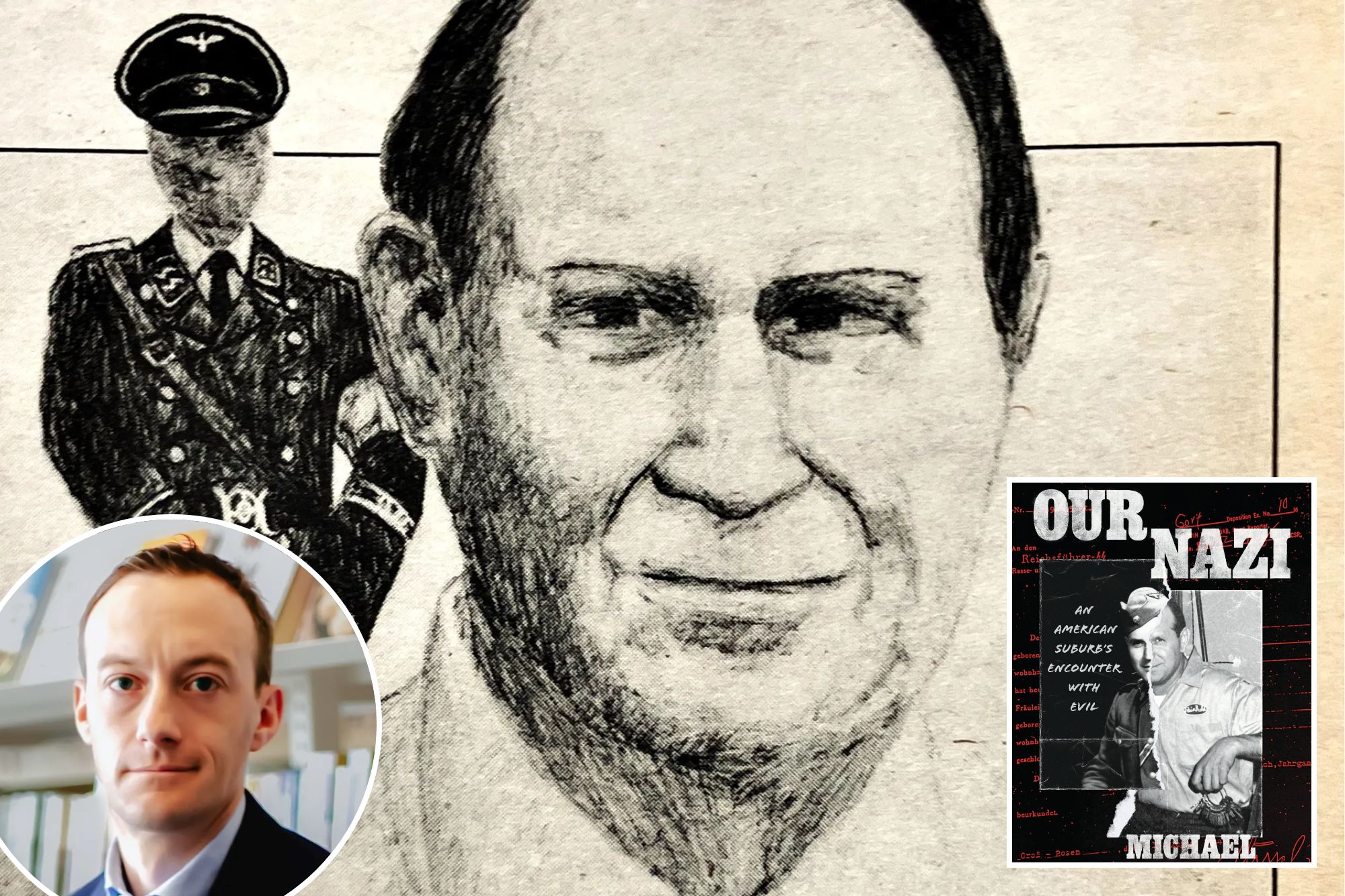

But as Michael Soffer reveals in Our Nazi: An American Suburb’s Encounter with Evil (University of Chicago Press), Kulle harbored a dark secret.

Throughout World War II, Kulle had not only been a member of the Nazi Waffen-SS, but had worked at the Gross-Rosen concentration camp where 40,000 Jews died.

Kulle was one of about 10,000 Nazis who entered the US after the war and, like the others, blended into his community, his neighbors oblivious to his past.

Born in 1921, Kulle was a member of the Hitler Youth before volunteering for the fighting wing of the Waffen-SS in 1940.

“Other boys in the Hitler Youth were wary of joining the SS, alarmed by the prospect of committing atrocities,” Soffer writes.

“The tower was intact.”

After joining the army, Kulle was wounded fighting the Russians and transferred to Gross-Rosen in his native Silesia, excusing him from front-line action.

Gross-Rosen was meant to be a labor camp, not a killing center like Auschwitz-Birkenau or Treblinka.

But it wasn’t like that.

“A compromise was made between the Nazi leadership: they would kill the old, the young, the sick and the weak, and any Jews who remained fit for exploitation would be sent to labor camps like Gross-Rosen, ” he writes.

“Then they would also be killed.”

Kulle rose through the ranks at Gross-Rosen, overseeing the construction of a new crematorium.

But by the spring of 1944, overcrowding meant there were over 40,000 prisoners instead of the maximum 13,000.

“The sewage system was overloaded and fecal matter was flowing into the stream that supplied the prisoners with drinking water,” writes Soffer.

“Even the new crematorium couldn’t keep up.”

When the war ended in 1944, Congress passed the Displaced Persons Act (DPA) in 1948, making it easier for immigrants to enter America.

Tower saw an opportunity.

After being granted a visa, Kulle, wife Gertrud, and children Ulricke and Rainer were allowed to enter the United States.

After docking in New York in 1957, they headed to Oak Park, near Chicago, where, in 1959, he took a job as a custodian at Oak Park and River Forest High School (OPRF).

He was the perfect employee.

Reliable and hardworking, nothing was too much trouble for Kullen and in 1963 he was promoted to head night warden.

“In high school Kulle was irreplaceable”, writes Soffer. “He was a favorite of every faculty member.”

Soon, Kulle and his family settled in a bungalow. “He slipped into obscurity, just another blue-collar worker in Middle America with a thick accent and an untold past,” adds Soffer.

He wasn’t the only Nazi in the neighborhood.

Albert Deutscher lived in nearby Brookfield.

During the war, Deutscher “had shot and killed hundreds of unarmed Jews, including children,” Soffer adds.

“His neighbors never suspected anything.”

In December 1981, the Office of Special Investigations (OSI), created to deport Nazi war criminals, formally charged Deutscher with war crimes and falsifying his visa application.

A few hours later, Deutscher stepped in front of a train.

While Deutscher’s neighbors expressed disbelief, Kulle knew the net was closing.

In the summer of 1981, OSA investigators began “DORA” (“dead or alive”) checks on suspected Nazis, including “a former camp guard from German Silesia: Reinhold Kulle.”

In July 1982, Kulle, now 61, received his first correspondence with OSI, and when he met with prosecutor Bruce Einhorn, he knew the game was up.

They had everything from Kulles’ personal SS file to his handwritten marriage application detailing his Nazi credentials. “They also had photos of Kulles in his SS uniform,” adds Soffer.

Kulle claimed that all he did was escort the prisoners around Gross-Rosen and he had never killed anyone.

But he had lied on his visa application.

This alone was grounds for expulsion.

When, in December. On 4, 1982, the Chicago Sun-Times ran the story: “Deportation bid on Suburb Man,” the game was up. “After decades of practiced silence, the secret of the Tower was now public,” writes Soffer.

As the story reverberated through the community, many wanted him gone.

But the startling numbers backed him up.

The school board even received an anonymous letter, apparently from faculty members, urging Kulle to stay.

After much discussion, Kulle was placed on final leave in January. 24, 1984.

“By now, there was no longer a Nazi working at the school,” Soffer says.

Meanwhile, in November 1984, Judge Olga Springer ordered Kulles deported, but it would be nearly three years before the decision was upheld by the Court of Appeals.

In October. On 26, 1987, Kulle was flown to Chicago’s O’Hare Airport and boarded a plane to West Germany.

“He landed at 12:45 a.m. Tuesday and headed to a relative’s house in Lahr, the city he left thirty years ago,” Soffer writes.

Kulle lost touch with most of the friends he made in Oak Park.

The only reminder of his time there came via a monthly pension check from the Illinois Metropolitan Pension Fund. “He almost lived long enough to face the charges,” adds Soffer, “but these pension payments stopped in 2006 when he died in Germany, still at large.”

#Meet #Nazi #hid #plain #sight #suburban #Chicago #years

Image Source : nypost.com